For me, Diplomacy is an addictive quarantine hobby. For my high school frenemy, it was training for the Trump administration.

OCTOBER 23, 2020, 7:00 AM

In the absence of parties and happy hours and date nights, millions of Americans living under lockdown have regressed into pastimes like playing Animal Crossing, reading War and Peace, baking sourdough bread, or attempting to learn Romanian.

For me and around two dozen friends, the diversion of choice has been Diplomacy, the strategy board game invented by a Harvard University undergraduate named Allan B. Calhamer in the 1950s, mass-marketed by the game company Avalon Hill, and eventually developed into an elaborate (and mostly free) online hobby. My friends, some of whom had never played before the COVID-19 pandemic, have quickly become hopeless addicts. For me, Diplomacy has been an on-and-off obsession since high school, when I played it at the home of one Michael Ellis, then a young conservative, and now an obscure but potent player in the Trump administration. The lessons the game taught both of us stuck, but in very different ways.Trending Articles

If you’ve never played Diplomacy, it might be hard to explain its appeal. The game is not for everyone, but it is ideally suited for the kind of nerd who has a deep interest in international relations, geopolitics, or really politics of any kind—Foreign Policy’s readership, in other words. This is a game for people who dream about power in its purest form and how they might effectively wield it.

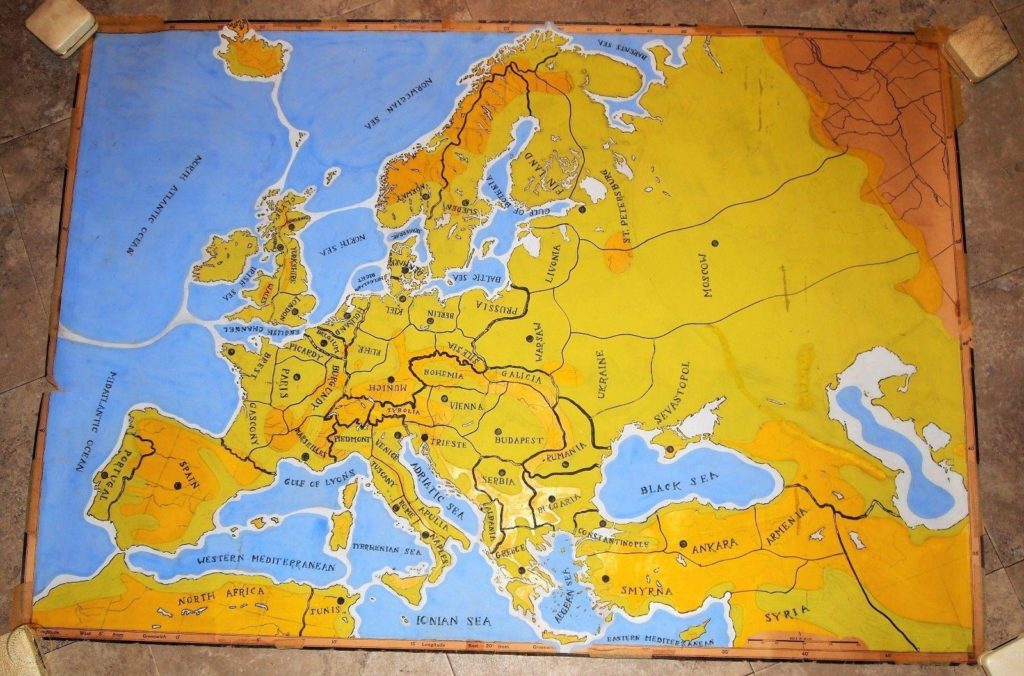

Beloved by President John F. Kennedy and former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, Diplomacy models the realist view of international relations—in which sovereign states rationally compete for spheres of influence, eventually achieving a stable balance of power. The classic version of the game is set on a simplified map of Europe in 1901, at the height of the rivalry among the great imperial powers—England, France, Germany, Italy, Austria-Hungary, Russia, and Ottoman Turkey—that would eventually culminate in World War I. There are no dice, unlike in other classic strategy games like Risk or Axis & Allies, and there are only two types of game pieces: armies and fleets. Everything about Diplomacy is simple and easy to learn, but the actual gameplay is fiendishly complex, built around social interactions between seven committed players, each pursuing their own selfish interests through a series of ephemeral military pacts.From left: a classic Diplomacy board; a January 1974 cover of Games & Puzzles magazine featuring the creator of the strategy game, Allan B. Calhamer; and a version of the game designed by David Klion and Manoli Strecker set in a near-future post-apocalyptic New York City. COURTESY PHOTOS

Part of what keeps Diplomacy interesting is its versatility—there are dozens if not hundreds of variant maps spanning regions and eras. In recent months, my friends and I have played variants set in the Western Hemisphere of the 1840s and in a near-future post-apocalyptic New York City, and we are currently deep into a 21-player global-scale variant set in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars (we designed the last two of those ourselves). But the spirit of the game is rooted in that pre-World War I moment when the Western imperial powers coldly, amorally divided up the rest of the world between them while maneuvering for strategic advantage in Europe—a fun, gentlemanly board game for them and a series of massacres, genocides, and myriad other oppressions for millions of people on every continent who didn’t get to play. There are no moral or ideological distinctions among the great powers; aside from geographic circumstances, one plays the German kaiser, the British prime minister, or the Ottoman sultan exactly the same way. Diplomacy encourages its players to imagine themselves as grand negotiators redrawing borders with international peers at a summit, not as rulers charged with upholding any set of religious, national, or democratic values.

I bring all this up not to “cancel” Diplomacy, without which my quarantine would be a great deal more monotonous, but simply to note why it might be considered good preparation for being a political operative in Washington.

I bring all this up not to “cancel” Diplomacy, without which my quarantine would be a great deal more monotonous, but simply to note why it might be considered good preparation for being a political operative in Washington. As the name implies, most of the game is spent negotiating—forming secret alliances, divvying up proposed territorial gains, playing rival powers off one another, and spreading disinformation. Each player submits secret orders, which are then revealed and executed simultaneously, after which negotiations resume (repeat ad nauseam). There are no formal penalties for lying to another player, though one’s reputation may suffer, and the damage can outlast any one game. Diplomacy is famous for ending friendships; as a group activity, it requires opt-in from players who are comfortable casually manipulating one another. It’s certainly possible to possess such skills without deploying them in one’s career—as a freelance writer, my own manipulations extend only to guilting my editor when I see he’s playing online video games on Steam. But should one wish to enter the upper echelons of Beltway politics—the cynical world of This Town, the proverbial swamp that President Donald Trump pledged to drain and instead naturally adapted to—Diplomacy is an ideal training ground.

In a satisfying game of Diplomacy, where nobody flakes out because of other commitments, shifting great-power blocs will gradually whittle Europe down from seven powers to a more manageable four or three, who will then agree to a draw—or fail to do so, thus paving the way for a solo victory by the most ruthless player. Classic Diplomacy requires exactly seven players, no more and no less, and each must be willing to commit a large block of time to the game. In person, this might mean a chaotic afternoon at a house big enough for multiple players to pair off in separate rooms for scheming. The combination of a global pandemic and the internet makes setting this up much easier. There are free websites, such as PlayDiplomacy or Backstabbr, where strangers or groups of friends can arrange games to be played out over multiple weeks, with orders submitted every 12 or 24 hours and thus plenty of time for lengthy correspondences by email, phone, text, or direct message.

But if you’re a teenager, the time commitment needed for an in-person game is a lot more plausible. My own teenage Diplomacy frenzy took place two decades ago and almost exactly a century after the classic game is set. Our little clique, spread out among several D.C.-area high schools, would meet at Michael Ellis’s house in suburban Maryland and spend whole weekend afternoons plotting and backstabbing while totally sober. (We were very cool.) I’m still friends with a few members of that crowd, but not with our host, who in a narrow sense has gone on to greater success and influence than the rest of us—an achievement reached, perhaps, by fully internalizing Diplomacy’s cynical realpolitik.

David Klion

Global Diplomacy 1821 map created by David Klion and Manoli Strecker